SQL Server corruption usually happens when a data page is written to disk and the disk subsystem doesn’t write what SQL Server expects. Or it does write what is expected, but somehow changes it before the next write. As one can imagine, this should really never happen.

But once is a great while it does. This post will show how page verification can help determine there is corruption before a DBCC CheckDB finds it. This early warning system can be very effective.

What is Page Verification?

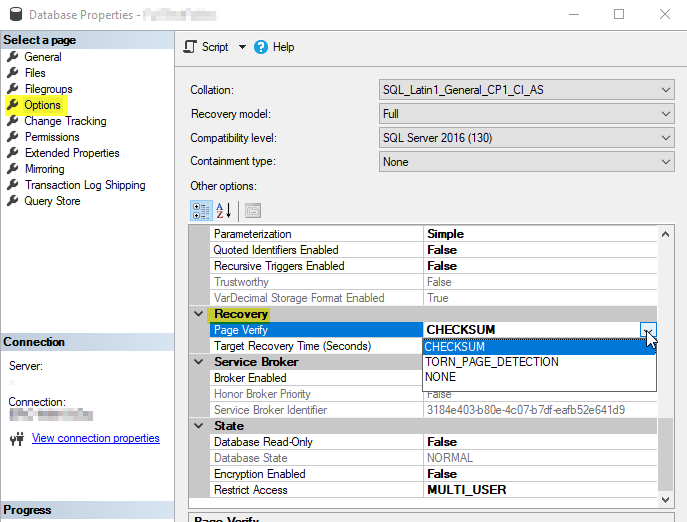

Page verification is a process in SQL Server where the engine writes extra data to the header of the page while writing it to disk. This extra data can be used to verify that the data later read from that page is what was expected. There are 3 options for the setting. They are NONE, CHECKSUM, and TORN_PAGE_DETECTION. The torn page option is deprecated. It should not be used and will not be covered in this series.

When set to CHECKSUM SQL Server will quickly determine a checksum for the page of data and write it to the header of the data page. Any time from that point forward when the page is read from disk SQL Server will perform the same checksum calculation and compare that to to the stored value in the header of the page. If the value matches that would indicate there is probably not corruption. If the values do not match that would indicate there is almost certainly some kind of corruption.

When set to NONE the checksum is not calculated and therefore not stored during a write. Since no checksum was written there is nothing to check on a read.

When enabled, the CPU overhead for these 2 checksum calculations is minuscule. There is no disk overhead as data page doesn’t change in size — it remains 8kb. The space used to store the checksum will simply be left blank in the header of the page when set to none.

The value of the setting can be set either in the SSMS GUI as a database property or by using T-SQL.

ALTER DATABASE MyDatabase SET PAGE_VERIFY CHECKSUM | NONE WITH NO_WAIT

Let’s see how this works.

In order to follow along with these demos, please create 2 corrupt databases using the information at this link. For this demo I’ll name them IsItSafe and HowCanIKnow. Include one additional step not mentioned in the creation link. After creating the databases and before entering the data set IsItSafe to NONE and HowCanIKnow to CHECKSUM for page verification.

Welcome back!

We now have 2 databases, both have been corrupted identically, but one has page verification checksums enabled and the other does not. Let’s start by running this query.

SELECT * FROM IsItSafe.dbo.SomeNames

The result is pretty disturbing. Even though we inserted Eric Edwards into the table, due to a disk malfunction, we are being given the name Eric Johnson — a value that was never entered into the database.

If we run the same query from the other database…

SELECT * FROM HowCanIKnow.dbo.SomeNames

Since our corruption changed the data value, but didn’t also write a new checksum, the database engine finds that the checksum calculated on read does not match the existing version previously written to the data page and reports an error. This is our desired outcome as delivering the wrong data is the worst possible outcome for most systems.

Upon seeing this error the next step would be to use DBCC CheckDB to repair the error — something that will be covered in a future post of this series. But first there is more to learn about checksum validation. The next post in this series will pick up exactly where this one left off and will cover using these checksums to validate the pages during a database backup.